CHAPTER 12

Freshly divorced, Lindy was introduced by new buddies to the nomadic life of a tree planter.

Canada is a resource-extraction country. Timber tops the list for perceived endless revenue streams. Trees were felled in multi-mile clear-cut tracts, the soil left scarred and barren. To sustain this, industry contracts were awarded to companies for the replanting of seedlings that decades later would become new forests. In British Columbia alone, there have been more new trees replanted than there are people on earth.

The lifestyle of a tree planter appealed to Lindy on several levels. Determined to be the good father he never had, this vocation required his working only sIx months out of the year. Winters could be spent hanging out with his sons, playing and traveling the country. Planting trees in the rugged mountains renewed his soul.

Tree planting camps, located miles away from towns on washed-out skidder trails, drew a colorful assortment of men and women looking to get paid according to their efforts, without a lot of oversight and bossing around. A newbie got trained and then assigned a tract to revegetate. No breathing down necks. Personal rhythms could be achieved while feeling the embrace of the always glorious and changing surroundings, replete with wildlife of every size and variety.

Before dawn, with the ringing of the chow bell, the rag-tag array of tents spilled yawning workers out of cozy sleeping bags. Camp cooks whipped up mountains of high-calorie-laden breakfast foods. Lunches were packed. With full bellies, as the sun barely crept over the mountain, vans held together mainly with bailing wire and duct tape were boarded for transport to the barren harvested area of the day.

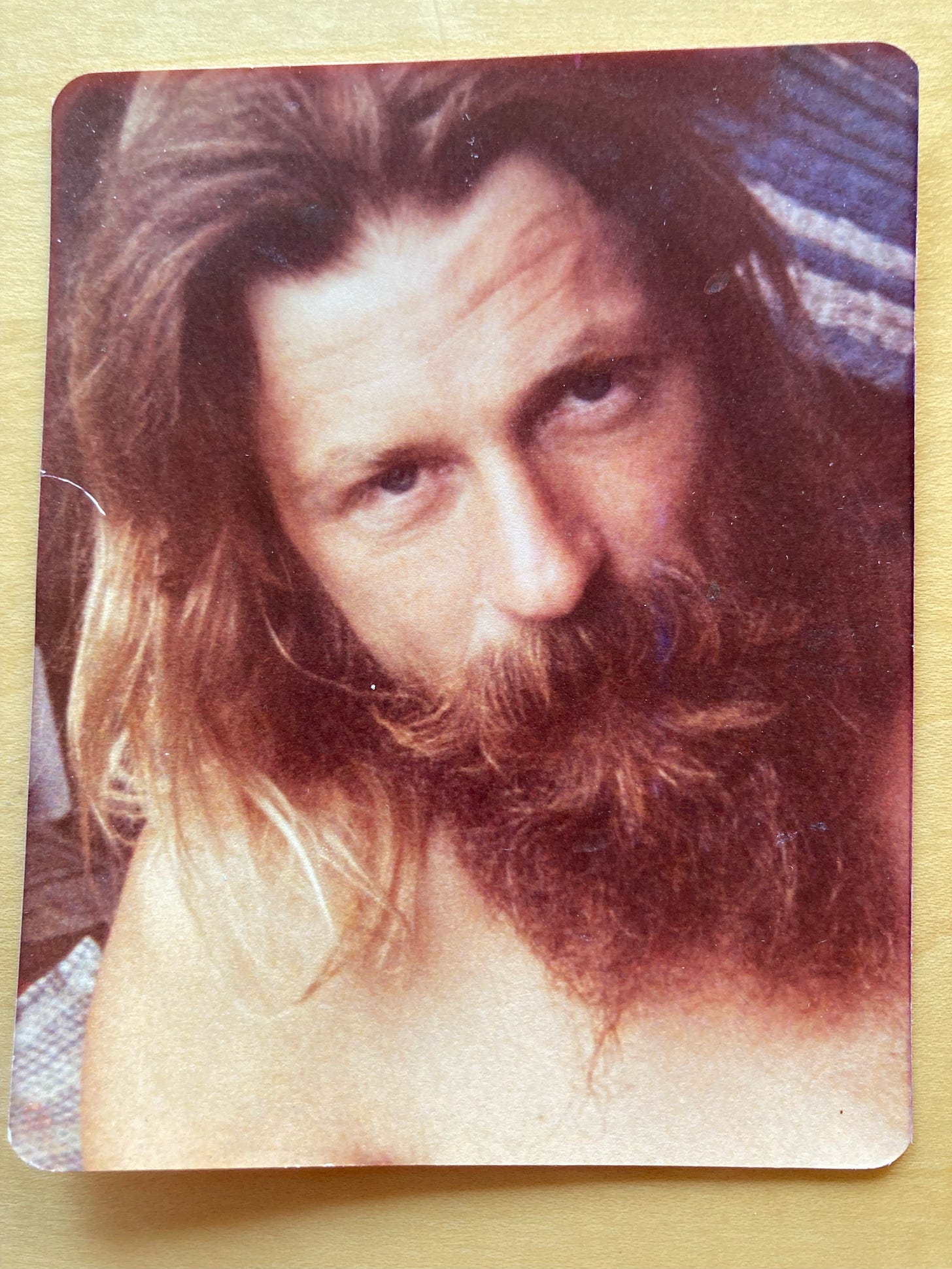

Tree planting paid twenty-five cents per seedling, not much money unless you really hustled. Lindy, tall, lean, with the agility of a mountain goat, sometimes planted one thousand wispy roots in a single long day, surpassing any paycheck he ever made before. By carefully allocating his summer earnings, he could make his money last until the following season. Tree planting seemed a custom fit for him.

His frugality genes inherited from his father paid off. Clothes bought at ‘the Sally Ann,’ the generic name for Canada’s thrift stores, vegetarian foods grown by family and friends, and driving a 25-year-old rattletrap, enabled Lindy and his boys to enjoy a degree of rustic comfort most of the time.

1978 brought welcome but totally unexpected news. Jimmy Carter, newly elected President of the United States, fulfilled a lofty goal. He campaigned on the platform of healing the nation’s wounds concerning wrongs committed with the invasion of Vietnam.

On the very first day the new President took office, he granted clemency to all the wayward soldiers hiding abroad. Against all odds, they could finally come home.

From a phone in a small box affixed to a large tree on the side of a desolate road, he made a collect call to California. “Oh sis, listen to this.” She could hear the glee in his voice as he read her the letter from the U.S. government. “Can you believe it? Carter granted all us bad boys amnesty. But,” he questioned, “do you think it’s for real? Can I trust it’s not a trick? Damn I’m scared of going back to prison.”

Speechless for a moment at this latest turn of events, she finally replied after taking several long shaky breaths, “Wow, it does seem too good to be true, but Carter’s a good guy. This is great news, bro. Oh god, I miss Mom,” his sister’s voice cracked. “She would be deliriously happy to know you are going to be really and totally free soon.”

He would be coming home curtesy of the Army. After arriving in the United States Lindy was flown to Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, for a debriefing session, where he accepted his Dishonorable Discharge papers.

In the United States, the consequences of coming out of the armed services with a Dishonorable Discharge were manyfold. You would never be able to vote, get a government job or loan, or own a gun and would be denied any kind of loans for school tuition. The designation also carried a red flag to prospective employers, many of whom thought twice about hiring a trouble-making nonconformist.

His papers stated he’d been discharged for misconduct and desertion, not mutiny, and for that he was relieved. He was also grateful to be living in Canada and was free from the restrictions of that label.

The next winter, legal passport in hand, head up, with a rightful sense of vindication, Lindy and his eight-year-old son Poppy traveled south over the border and arrived in California at his sister’s doorstep.

Women, women, women. Three more reasons Lindy enjoyed tree planting.

There were women cooks, women planters, women partners of planters and a few groupie women who just liked the gypsy life. Though in the minority, these few rugged, hardworking women also enjoyed the thrill of wild adventures and the independence tree-planting experiences offered. All genders calling tree-planting camps home enjoyed evenings watching the late setting sun finally creep behind western peaks, which brought out guitars, harmonicas and vicious chess games.

After accepting collect phone charges from remote communities in the vast northerly part of the continent, Lindy’s sister Carol delighted in the stories of his love of the moment. Serially monogamous, his amorous reports were ongoing with each call.

One particular woman he talked about, a fellow tree planter and devout follower of an east Indian guru named Bhagwan, was especially colorful, and that wasn’t just metaphorically speaking. Followers of Bhagwan were summoned to wear clothing of rainbow hues. Flowing robes of reds, purples and oranges were the favored attire. Initiated into the cult when she’d made a trip to India, she was planting trees to earn money for a return ticket to his ashram. Her tales of India initiated Lindy’s of dream of meeting Kirpal Singh, the Indian guru he adopted for himself while in prison.

In 1980, he and his rainbow-hued woman embarked upon a several month winter trek to India, the most crowded country on earth. Upon arrival, they were surprised to learn that her guru Bhagwan had migrated to the United States the previous month, and that Lindy’s inspiration, Kirpal Singh, had died suddenly. They regrouped. Disappointed, they commenced traveling the vast country with no particular goal in mind.

Exploring India, Lindy found himself disgusted sometimes, and delighted at others. Experiencing India was a wholly different side of life.

Hi Carol … Hotel Rockholm, home of the best ten cent a cup coffee in India, treats us to views of crashing monsoon breakers on rocks below my chair, fishing boats with black sails, up like scimitars etching and cutting the trade winds. Was drinking gin a while ago with a man who came from one hundred miles north to enjoy the solitude and beauty of the Arabian Sea.

The fishermen here are laying waste to the countryside, and me, a tourist who comes from a place where corporations are already doing a fine job of just that, watches. Dead turtles, snakes and eels, are strewn all over most beaches. Thousands of kids run around dodging shit of the hordes of homeless dogs. Richshaw drivers wave madly at us trying to manipulate their hello’s into rupees. “Your country?” ask punky guys in antagonizing tones, looking for a fight. Here, everyone fights for everything. India’s beautiful, but it’s not pretty.

We saw a little boy in the bus depot the other day whose eyes were gouged out by his parents so they could be better beggars. His sister was pinching him so he would cry, to glean even more sympathy. It really drove home that man’s inhumanity to man, even to his own children, knows no bounds. I tried to imagine how desperate one would have to become to do such a thing, and the mere thought about tipped me over.

We’ve also visited Varanasi, which perhaps is the oldest city in the world. Every kind of beast, beggars and corpses co-exist together among piles of garbage and grime. The place is a sort of entrance into a parallel universe. They burn dead people on steps 24 hours a day. It takes 3-4 hours for fire to consume a body, with 5-10 always flaming away. They’ve been doing it for thousands of years, while dolphins swim gracefully offshore.

Soon we’ll leave this land of amazingly glorious flowers, elephants, and the wacky world of all the various monkeys that claim their rightful place in society and are honored for such.

Can you pick us up at the L.A. Airport? I’ll call when we arrive in the U.S.

Your humbled brother Lindy Ragamuffin

Lindy’s distain for the uber-wealthy and his already skewed vision of social justice in the world came into further focus after the visit to India. Later, his traveling to poverty-stricken countries in South America left any sense of a fair moral compass permanently skewed.

Life wasn’t fair. That topic ingrained from childhood occupied much of his thinking. In one particular dinner conversation, he remembered lamenting to his family how sad it made him to witness homeless people, dressed in rags, begging for money, and watching passersby turn their heads away. “Why don’t they get jobs, so they could live in houses?” he asked.

“Your question implies the playing field is level,” his father informed him. “It’s not. The circumstances of one’s birth almost always predict the outcome of one’s life.” Lindy’s father Gene saw confusion in his son’s eyes. “Plain and simple, there are the haves and the have nots. Those born into families with pockets full of gold always want more. A few alms are allocated to the masses, so they won’t overthrow the rulers, but never enough to change any outcomes. We’re told our country is different because our founding fathers declared ‘all men equal’. But are they?” he asked rhetorically. “Laws were written by the wealthy for the wealthy. I think you will agree, for example, that women, people of color, and those born into poverty are not equal,” he suggested, tipping his head, eyes implying doubt. “If opportunities for upward mobility were available for all, equality might be achieved. But they’re not, I’m sorry to say.”

In remembering that conversation, Lindy questioned whether his personal observation of a system rigged was one he cared to participate in at all.

Tree planting did not present itself as a career path. The average length of time employed burying seedlings on craggy terrain was five years. Stoop labor favored short people. Lindy, standing at six feet four inches, weighing in at a mere 170, had a long torso built for pursuits best suited for remaining in an upright position. Running, basketball or cerebral pursuits would have suited his body better.

Definition of tree planting: the repetitive motion of bending over, slashing at rock-hard soil with a special tool called a Pulaski, gingerly easing a seedling into the hole and covering it, all in one fluid motion. Move eight feet and repeat, repeat, repeat. Bare root saplings come in units of 100, carried in a heavy canvas back pack, straining frail spines even further.

After five years, Lindy, pushing limits leaping from one rugged spot to another in ten- to twelve-hour daily stretches, felt his body taking the toll. His long core, constantly bending and digging, suffered ruptured back and neck discs. As they bulged, it put pressure upon fragile spinal cord nerves, causing constant pain. Curiously he wondered why the muscles in his arms and legs tingled and spasmed, robbing him of sleep. He pushed through. He saved his money.

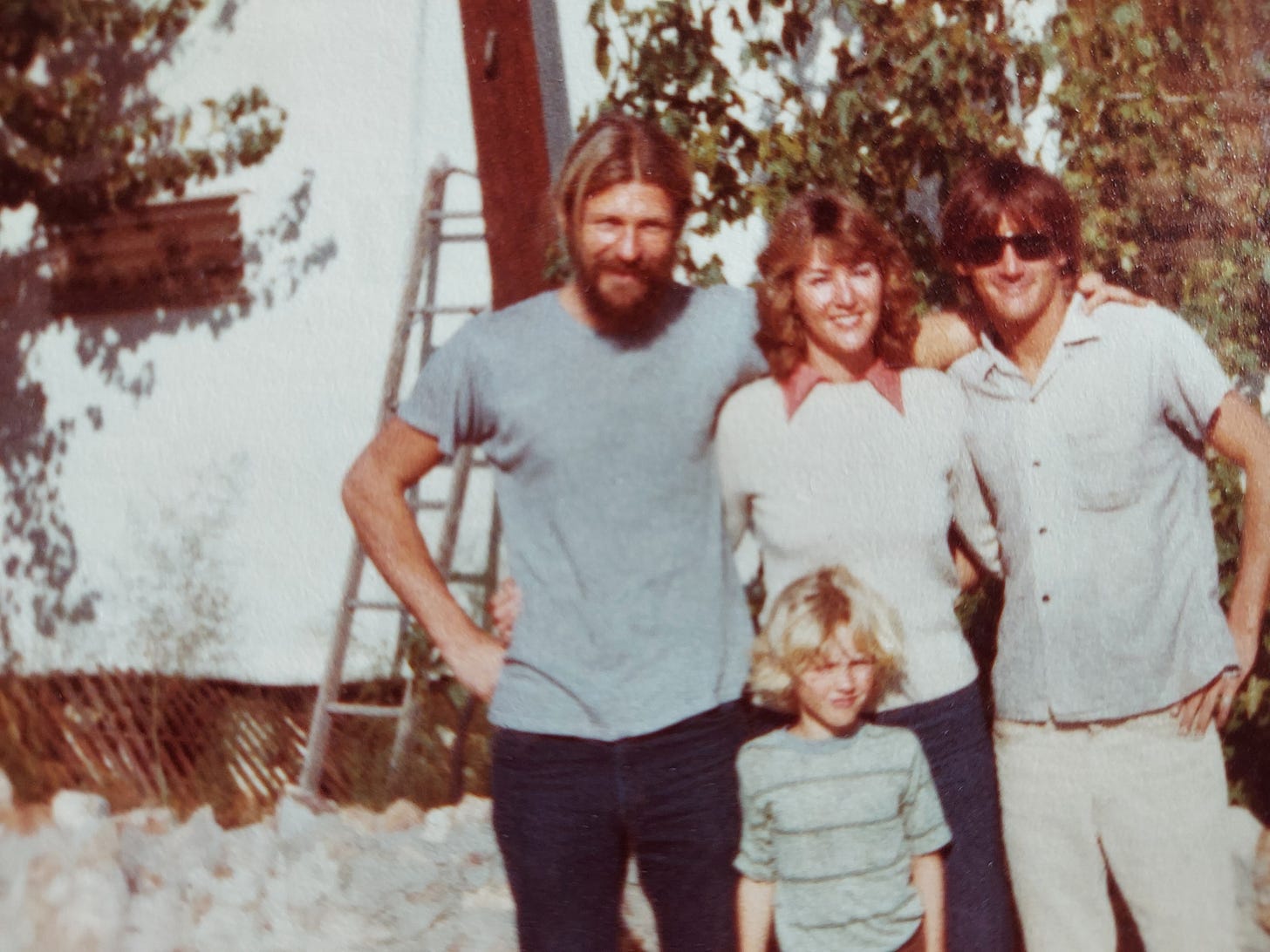

The next winter, he drove his family, consisting of his colorful girlfriend and sons aged 8 and 12 south to spend the gloomy Canadian months in sunny California at his sister’s house for a much-needed rest.

His sister, shocked to see him dragging his left leg, and wincing when performing the smallest of tasks, knew his tree planting days were numbered.

Loved seeing the pictures of all of you!

Loved seeing the pictures of all of you!

I had forgotten the tree planting and how hard it was on the body!